Diana Jarman

"One crowded hour of glorious life is worth an age without a name".

I am very grateful to the Second World War Experience Centre S.W.W.E.C. for helping me to tell the story of Diana Jarman on this page. Copyright © and courtesy of S.W.W.E.C. unless otherwise indicated.

John and Diana Jarman Wedding

One of the most tragic stories was that of Diana Frances Jarman, wife of Captain John Denis Jarman, 2/16 Punjab Regiment, Indian army who was killed in action in the defence of Singapore Island on 12th February 1942, although at the time, his wife believed him to be a prisoner of the Japanese.

Diana was born on 18th June, 1921, Quetta, Balochistan, British India (now in Pakistan) she was the daughter of Lieutenant Colonel H. E. Tyrrell and Mrs Tyrrell of Jubbulpore. Lt. Col. Tyrrell was the Commanding Officer of the Battalion in which John Jarman was a Subaltern. Initially, her parents felt they were too young to marry, however, with the war and the regiment being posted to Malaya they relented and the two were married in October 1940 and after the briefest of honeymoons, he then left for Malaya. He returned to India for a short leave at the end of December 1941, leaving there again to join his regiment in Malaya in the middle of January.

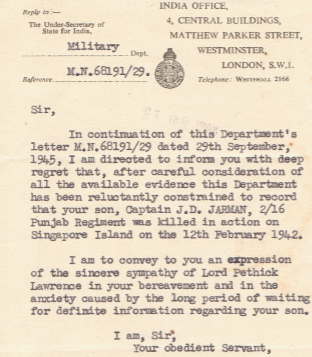

Death Notice, Capt. John Jarman

After the Japanese invasion and the fall of Singapore, Diana had no news of her husband or her father (In fact her father had been taken as a prisoner of war by the Japanese but did survive his imprisonment in Changi). She therefore wrote to her mother-in-law (John’s mother) in September 1942:

Dearest Mother,"I haven’t told you my news because I wanted to be quite sure. I am coming home! I see no point in staying here now – I’ve had no news of John yet – and I feel I might just as well be at home. I am so excited about it. I do hope you will be pleased. I’ll try and cable you when I leave. I hope it will be soon – but I’ve heard nothing definite. Anyway, I shall be with you at Christmas. "

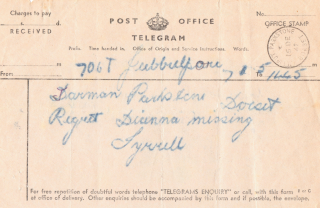

In October 1942, just two years after her wedding, she sailed from Bombay in the CITY OF CAIRO. They reached South Africa safely and she telegraphed "Arrived Durban. Will cable again later – Jarman." The cable was received on 24th October but nothing more was heard from Diana. However, Mrs Jarman did receive a cablegram from her daughter-in-law’s mother, from Jubbulpore, on 16th December 1942, "Regret Diana missing. Tyrrell. "

Telegram - Diana Missing

Unknown to both families, while on the second leg of the journey from South Africa to England, the ship was torpedoed by the German submarine, U-68. Diana made her way independently to Lifeboat No.3, but a second torpedo smashed the boat as it was being lowered and she was thrown into the water. However, she managed to swim to boat No.1 and the majority of passengers did succeed in reaching one of or other of the boats. Both the Captain and the Chief Officer survived to take charge and they decided to make for St. Helena. There was a compass in every boat but only one sextant. They therefore sailed independently during the day but rendezvoused at night.

The Chief Officer, Britt, was in charge of boat No.1 but it was overloaded with 54 passengers and crew (including Diana). Many people in the boat required bandaging and first aid and with Stewardess Annie Couch’s help, Diana was able to attend to them all. "Stop calling me Mrs Jarman, " she told them. "Call me Diana. " A quartermaster who survived, Angus MacDonald, wrote of her "The youngest person among us, Mrs Diana Jarman, one of the ship’s passengers, and only about twenty years of age, was a great help with the first aid. She could never do enough, either in attending to the sick and injured, boat work, or even actually handling the craft. She showed up some of the men in the boat, who seemed to lose heart from the beginning. "

Open Boats Meet

Author's File

The Captain believed that the boats ought to keep together as only in that way could they all be sure of following the right course. However, Britt wished to go on ahead and get help as his was the fastest boat. At the same time, it was the most porous, needing constant bailing and because it was carrying more people than it was designed for there was a shortage of rations. Reluctantly the Captain agreed, and No.1 boat pulled ahead – not to be seen again. The other boats reached St. Helena after 13 days covering about 670 miles and there some 148 survivors landed.

In Britt’s boat all went well until the tenth day, by which time it was felt they should have sighted the island. With the consequent slump in morale, the lack of food and water and the strain of surviving in an open boat, there came a number of deaths. Jack Edmead, one of the ship’s stewards kept a diary of events. He and MacDonald relieved the dead bodies of their effects before burial, recording the details and Diana kept all they collected in her emergency bag in the stern. However, Britt himself then became mentally deranged and soon afterwards died. MacDonald took over the navigation but he found that the navigational details were only good up to the tenth day and then they degenerated into mere scribbles. They had no real idea as to where they were.

By the end of the third week only eight were left alive out of the original 54. They caught a dog-fish but found it quite inedible. So, with no water and little food, by the end of the fourth week there were only five. Two more died shortly after. One man took the plug out of the boat several times when nobody was looking. He was eventually caught but he then argued that as he was going to die, there was no reason not to pull the plug out as then they would all die together.

Finally, on December 12th, 36 days after the CITY OF CAIRO had been sunk, the life-boat was sighted, ironically, by a German blockade runner, the RHAKOTIS. The rest of Diana’s story is probably best told in the words of Angus MacDonald, the quartermaster.

We were well looked after and well fed on the German ship, and from the first day I walked round the decks as I liked. Jack (Edmead, the other survivor) was confined to bed for a few days. We were not allowed to visit Diana, but the captain came aft and gave us any news concerning her. She couldn’t swallow any food, and was being fed by injections. When we had been five days on the ship, the doctor and the captain came along to our cabin, and I could see they were worried. The captain did the talking, and said that, as the English girl still hadn’t been able to eat and couldn’t go on living on injections, the doctor wanted to operate on her throat and clear the inflammation. But first of all, he wanted our permission. I had never liked the doctor and had discovered that he was disliked by nearly everyone on board, but still, he was a doctor, and should know more about what was good for Diana than I could. So, I told the captain that if it was necessary to operate, he had my permission as I wanted to see Diana well again. Jack said almost the same, and the captain asked if we would like to see her. We jumped at the chance, and went with the doctor. She seemed quite happy, and looked well, except for being thin. Her hair had been washed and set, and she said she was being well looked after. We never mentioned the operation to her, but noticed she could talk only in whispers.

That evening at seven o’clock the captain came to see us, and I could see something was wrong. He said " I have bad news for you. The English girl has died. Will you follow me, please? " We went along, neither of us able to say a word. We were taken to the doctor’s room where she lay with a bandage round her throat. You would never know she was dead, she looked so peaceful. The doctor spoke, and said in broken English that the operation was a success, but the girl’s heart was not strong enough to stand the anaesthetic. I couldn’t speak and turned away broken hearted. Jack and I went aft again. It was the first time I had broken down and cried, and I think Jack was the same.

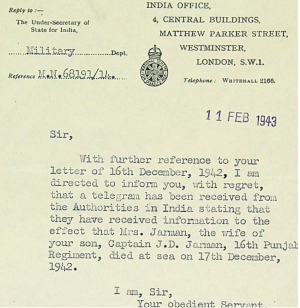

Death Notice Diana Jarman

The funeral was the next day, and when the time came, we went along to the foredeck where the ship’s crew were all lined up wearing uniform and the body was in a coffin covered by the Union Jack. The Captain made a speech in German, and then spoke in English for our benefit. There were tears in the eyes of many of the Germans, as they had all taken an interest in the English girl. The ship was stopped, and after the Captain had said a prayer, the coffin slid slowly down a slipway into the sea. It had been weighted and sank slowly. The crew stood to attention bareheaded until the coffin disappeared. It was an impressive scene, and a gallant end to a brave and noble girl. We had been through so much together, and I knew I would never forget her.

Of course, that was not the end of the story for the other two survivors. The RHAKOTIS, whilst crossing the Bay of Biscay, was sighted by a British aircraft and then sunk by HMS SCYLLA so the two were again shipwrecked. This time they went to different lifeboats. Angus MacDonald’s boat was picked up by a German U-boat and he spent the next three years in a Prisoner of War camp. Jack Edmead’s boat reached the Spanish coast and landed at Corunna. From there he managed to get to Gibraltar and so home to England bringing news of the CITY OF CAIRO’s missing lifeboat.

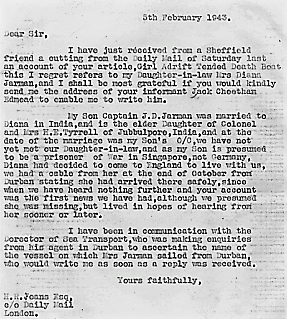

Letter to the Daily Mail

The first the Jarmans heard of what had happened to her was in a BBC news broadcast! The owners of the CITY OF CAIRO, Ellerman Lines Ltd., then wrote to Mr Jarman. After briefly recounting the sad story of Diana’s last voyage, the letter ended: It is much to be regretted that your grievous news was first conveyed to you through the press and the BBC. The first intimation we had of this incident ourselves was the account published in the Daily Mail. It appears that the press must somehow have had word of the steward’s arrival and were waiting for him at his port of disembarkation here and his story was out before he had got to the office to make his report. It is we think unfortunate that the Ministry of Information pass these stories before checking with interested parties.

Awards were given to both survivors of this boat, MacDonald and Edmead who received the B.E.M. Unfortunately, Diana was overlooked for a similar award - it could not be awarded posthumously but in another case, in another boat, an award was backdated to the day prior to death. But in Diana's case, no contrived back-dating was considered. In a citation of close on 1,000 words in the relevant London Gazette supplement Diana receives no mention, not even a commendation for brave conduct, it was an omission that was never corrected.

Here are some links to associated pages on the site: a survivor's report No.1 Boat Log written by Jack Edmead and an account by Angus MacDonald Ordeal